Planning for Homelessness

Currently within Australia, there are over 100,000 people 'sleeping rough'. The rate of homelessness is 49 out of every 10,000 with 44% of this population being female and 25% being indigenous Australians. This is an alarming rate which is growing exponentially each year.

|

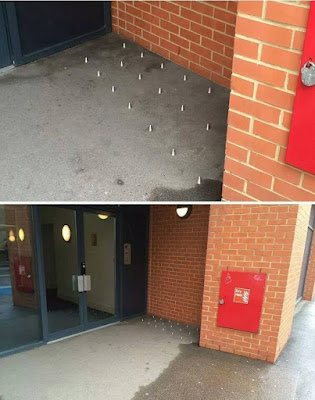

| Figure 1: Spikes appearing at a London Apartment Building (Source: Ethan Pioneer, 2014) |

|

| Figures 2 and 3: Public seating designed to deter prolonged use. (Source: The Atlantic, 2014). |

|

| Figure 4: Wall seating at a Montreal Railway Station (Source: The Atlantic, 2014). |

Draconian homeless deterrence strategies contradict the famous ideology of 20th century French socialist and planning academic Henri Lefebvre, who discusses the idea of the 'right to the city' and how inhabitants manage urban space for themselves.

Luckily, such preventative measures have sparked outrage amongst the local communities in which these measures have been employed. For example, London's mayor called the spikes "ugly, self defeating and stupid", and protesters poured concrete over a set of spikes outside a supermarket. A petition was also signed by nearly 130,000 people to removed the spikes from a London apartment building.

Whilst this response may restore your faith in humanity, little is being done by the Government to actually provide successful active solutions to prevent homelessness within out cities. Robert Pradolin (former General Manager for Frasers Property Australia and active public speaker against prejudices against homeless people) has teamed up with 'Launch Housing' in efforts to create pop-up rooming houses. The agency plans to convert vacant office buildings within Melbourne that are awaiting redevelopment into temporary accommodation for people struggling with homelessness. Their strategy includes equipping empty offices or vacant floors with pods constructed from temporary partitions that can be quickly dismantled when the property owners need the space back.

This idea of pop-up housing was recently discussed earlier in the year by housing and support services and City of Melbourne representatives, where Heather Holst (CEO of Launch Housing) said that pop-up housing might seem like a desperate response, but necessary given that homelessness was reaching crisis levels.

Obviously, the temporary housing would need to have existing toilet and showering facilities and would need to be altered so that they complied with the relevant rooming house safety standards, but this seems a worthwhile step in the right direction (particularly as some office buildings remain empty for years waiting on development, purchase, or the approval of planning permits).

Similarly, earlier this year a wealthy Melbourne family offered $4 million to construct 57 portable homes for disadvantaged people on vacant VicRoads properties in efforts to tackle Melbourne's homelessness crisis. The project is mostly being privately funded by philanthropists Brad Harris, who co-owns the Sporting Globe Bar and Grill chain of 9 restaurant-bars (and his father Geoff Harris, who co-founded Flight Centre).

The plan includes 57 pre-built studio units to be transported to 9 disused housing blocks along Ballarat Road within inner city suburbs Footscray and Maidstone, where a public acquisition overlay is in place should the government one day choose to widen the road. VicRoads has bought several properties along Ballarat Road in recent years in anticipation of the road widening project (The Age, 2017). The project is subject to development consent from Maribyrnong City Council, if granted, tenants can be expected to move in during the middle of this year.

|

| Figure 5: Artists impression of the new temporary housing units (The Age, 2017). |

So to conclude, the above examples impose some important questions: why does there seem to be a bigger response to homelessness from members of the public than from the Government? And is temporary housing the only solution to social housing?

Comments

Post a Comment